Fintech R&R☕️🏷 - The Price is Right. Or is it..?

A frank discussion about product pricing, reasons discovery and research is vital, popular pricing models in fintech and some of the fun psychology 🧠 behind pricing pages

Hey Fintechers and Fintech newbies 👋🏽

A busy few weeks of fintech news with lots of overlap with previous editions of Fintech R&R.

Last week, India’s Unified Payments Interface (UPI) transactions crossed the 10 billion mark. You can read my dive into this growing payment method, which could prove to be the first global Open Banking payment rail, here.

The same week also saw significant news from the Open Banking payments here in the UK, with the number of payments made using the network hitting 11.4 million in July, the most in a single month since its inception. My deep dive a few weeks ago covered how OB Payments works and some insights into how to accelerate Pay-by-bank adoption.

Then there’s the news from Twitter (I refuse to call it X). They’ve been granted payment licences from seven US states, which means Musk’s dream of a superapp could soon be a reality, giving Twitter the ability to process payments and allow creators and friends to send and receive money very much in the mould of WeChat in China.

This Twitter news reminded me about the uproar after the introduction of paid verification, and it’s this, as well as several relevant conversations over the past month, that led me to this week’s topic…Pricing.

I specifically want to talk about some of the different pricing methods and some of the psychology of pricing. Because folks have a tricky relationship with money at the best of times, but when it comes to convincing a customer to part ways with money for a service or product, let alone a service that stores and manages money or merely moves it, the relationship gets even trickier.

And in the pricing conversations I’ve had over the past month, I found myself starting sentences with ‘Product Pricing is complicated’. This will hopefully peel away a couple of those layers of complication.

So, as well as interesting news, puns + movie references, this edition includes the following:

Basic pricing strategies

Using an objectives-based approach

Different pricing models and the Fintechs that use them

The psychological tricks behind pricing pages

Forget about the Price Tag

“It’s complicated.”

A common status update made by Facebook users (mostly teenagers) to announce a change in relationship status or to invoke a bit of drama.

And a phrase I end up using before getting into the weeds of a pricing conversation. But why?

The complexity arises from the various factors that must be meticulously considered to strike the perfect balance between profitability and market competitiveness.

From the ever-shifting trends of consumer demand and the intricacies of production and customer acquisition costs to the influence of competitors and the psychological nuances of pricing perception. For fintechs who have multi-layered offerings with B2C and B2B embedded solutions (yes, I mentioned embedded finance so you can tick that off your invisible Fintech Bingo scorecard), the complexity is even greater as there are multiple pricing strategies for each product stream that include factors such as fixed setup costs, direct to consumer prices, interchange revenue, and transaction/request based pricing. That’s before you even consider who you’re selling to, as pricing an enterprise solution for a bank might be higher than an enterprise solution for a small fintech.

So, before jumping straight into adding a price tag, it’s essential to get clarity over critical inputs that will drive the pricing decisions.

Know Your Customer

This isn’t KYC in the onboarding and regulatory compliance sense. As I’ve said in previous editions, it’s the fundamental understanding of your customers from where they shop, everyday habits, demographics, and their problems.

Understanding the target customer is fundamental to creating a viable pricing model. Fortunately, for organisations who go through a rigorous discovery process and distil research using the Jobs to be Done framework, these insights are easy to obtain and use to drive pricing decisions.

Although ‘the customer is always right’ is a bit of an antiquated phrase nowadays, there is value in asking a small set of early adopters or an existing beta testing group some price-specific questions. Some of these may have been covered during that initial discovery phase, but it’s always important to get constant feedback, especially prior to a big market launch and ask questions like:

“Now you’ve used the product for X number of months, how much would you say you’d be willing to pay for it?”

“This product is similar to a similar product you’ve used that a competitor offers. In terms of functionality, do you think this product is more or less valuable than the following competitor products?”

“If I told you that based on your potential usage, this product will cost you £XXX per month, would you say a) That sounds reasonable, b) That’s a little more expensive than you’d expect, or c) It’s a little cheaper than you’d expect

NOTE: The questions are designed to form the foundation of a decision and not provide the exact price points themselves.

These are boilerplate questions but vital to gauge appetite for a price band and understand the starting point.

Another area where discovery assists the pricing process is understanding customer problems using the underlying research and applying the JTBD methodology. This highlights customers’ issues and motivations, which can then be used to inform pricing decisions and reduce customer friction once they get to the pricing page by using competitor comparisons and focusing on the value gain. Providing a solid foundation for a pricing model is another major benefit of a thorough JTBD exercise.

This strategy of pricing based on time-saved, increased efficiency or other broader benefits gained is called Value-based pricing.

The Bottom Line

An alternate pricing strategy is one that sets the price of the product offering primarily based on the costs associated with developing, maintaining, and delivering the software. In this approach, the company calculates all the expenses incurred in creating and operating the SaaS product and then adds a desired profit margin to determine the final price.

Some of the key parts of a strategy that looks at costs are as follows:

Cost Calculation: Calculate all costs associated with the product, including development and programming expenses, server and infrastructure costs, employee salaries, customer support and maintenance costs, software licensing fees, and any other overhead expenses directly related to the product

Fixed & Variable Costs: Grouping the above into fixed costs such as software development office space and variable costs such as server space or other user and usage-based costs

Profit Margin: The desired profit margin or markup after calculating the total cost. A common figure used is 80-90%, meaning if the total software costs are £100, then you’d charge £180

Tiers: Regardless of the scalability of the product, different customer tiers may require different levels of service, so tiering the prices and increasing the margin to factor in a potential increase in costs might be necessary

The strategy of pricing based mainly on underlying running costs + margin is called Cost-based pricing (AKA Cost-Plus pricing or Margin pricing).

While this is an excellent simplistic approach, it has limitations as it doesn’t consider customer value. This means the product could be underpriced vs. the value a customer perceives to gain from using it. This is why many use a combination of cost-based and value-based for their overarching pricing strategy.

Competitive Edge

Competitor pricing analysis is another vital input in the overall pricing of the product. Of course, competitor analysis is a bit tricky for new entrants into a market with a completely unique product, but most products will have something to compare to, even if the offering is different.

Understanding competitors’ pricing decisions is crucial, as pricing too high could lead to customers flocking to cheaper alternatives, while pricing too low might trigger concerns about product quality or sustainability.

Some use competitors’ pricing as a yardstick, and some align very tightly with competitors’ pricing, but either way identifying those closest comparable companies and continuously monitoring pricing is key as this is a dynamic, not a static arena changing with costs, customer needs and market factors such as inflation.

Objective Thinking

An important factor in deciding which single overarching strategy to go for or how to blend the various approaches is understanding the stage the business is at and its objective.

For example, a business entering a new and congested market may price itself at a discount to existing players, whereas a company in a market with no competition with a product that has demonstrated clear value would be priced very differently and much higher. The stage the company is at, and their objective at that stage, is a key factor in the pricing process.

Increasing Exposure/Entering a New Market

When the objective is to increase exposure in a market, pricing is usually at a discount vs. normal future prices and is usually slightly lower than competitors, OR the product’s value is more significant than competitors but at a similar price point. This differentiates your product offering and favours acquiring customers and increasing sales over maximising profits. In some cases, this means entering a new market and differentiating by providing a premium product and price.

EXAMPLE: A digital bank for High Net Worth individuals (HNWs) with premium service and equally premium prices.

Maximising Profits

The header speaks for itself.

It’s a more common objective for later-stage organisations that have found Product-Market fit, have a large and growing customer base and are looking to grow profit margin by reviewing their cost base and using more of a cost-based pricing model. This requires some A/B testing, though, as setting margins too high can lead to customer churn.

EXAMPLE: Difficult to call out, but certain payment intermediaries who know their cost per transaction and have slowly upped their fixed + percentage pricing model.

Promoting Future Sales/Customer Acquisition

This is where the objective is to have a higher initial customer acquisition rate, which then allows for increasing future sales of higher-margin products. This usually means pricing a product at a discount to cost with the aim of making up the margin difference on saleable add-ons or other products down the line. Traditionally known as the Loss Leader strategy.

EXAMPLE: An SME lender that provides cash flow analytics and insights at a discounted monthly rate but can then upsell lending products based on that data at market or above market rate.

Customer Retention

Some products have a high switching cost as part of their overall business objectives. Switching cost is the term to describe the expense, effort, and disruption a customer may incur when they decide to switch from one product to another. Although it’s less prevalent in fintech products, with many offering standard APIs, there are still areas where high switching costs are used to keep customers.

EXAMPLE: Merchant acquiring hardware with integrated terminal software and training for retail employees, ensuring lock-in and high switching cost. Square is an excellent example of this.

Horses for Courses 🐎💰

So, We’ve covered overarching pricing strategies and the different objectives that drive pricing decisions.

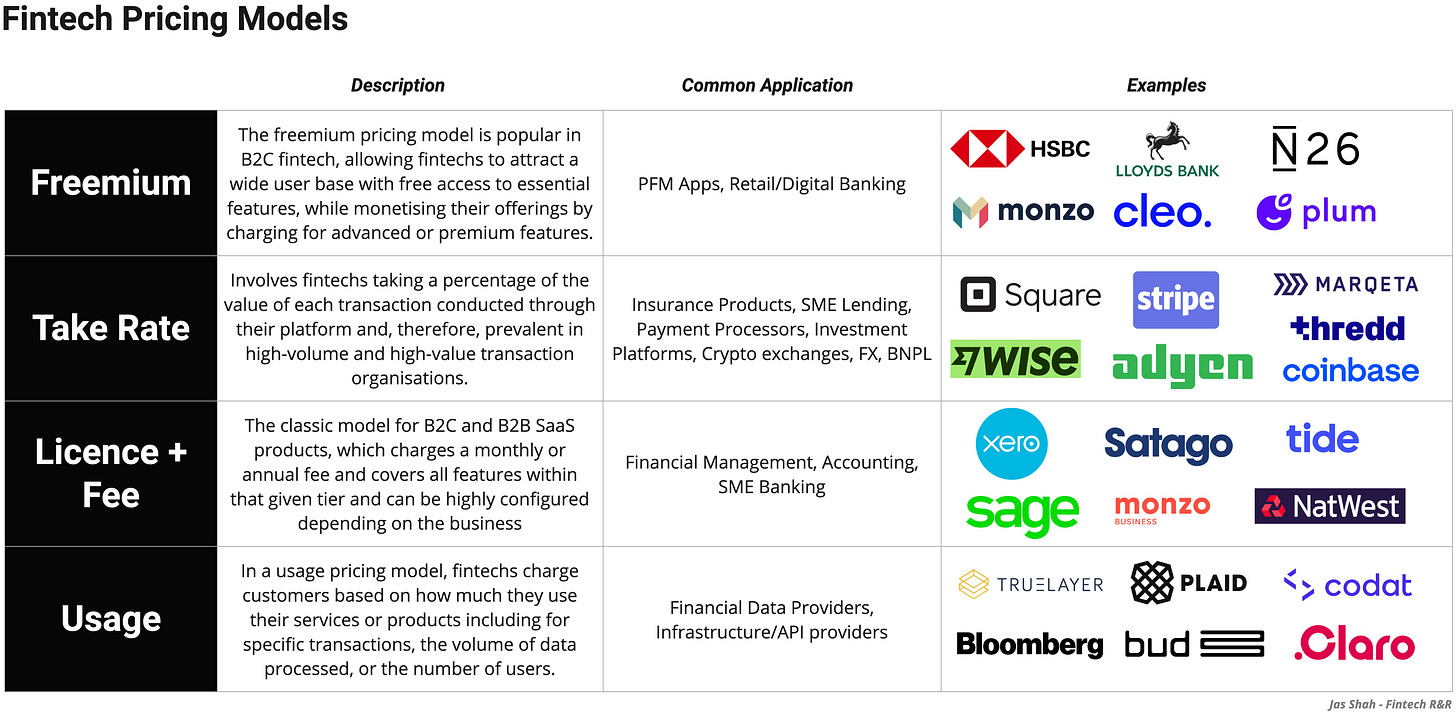

What folks reading this are most familiar with is the different models seen on the pricing pages of fintech offerings. At the very least, pricing models such as the Freemium model and Licence + Fee models.

These are just some of the models used across B2B and B2C fintechs, but there are more and different categories of fintech that tend to gravitate to different models.

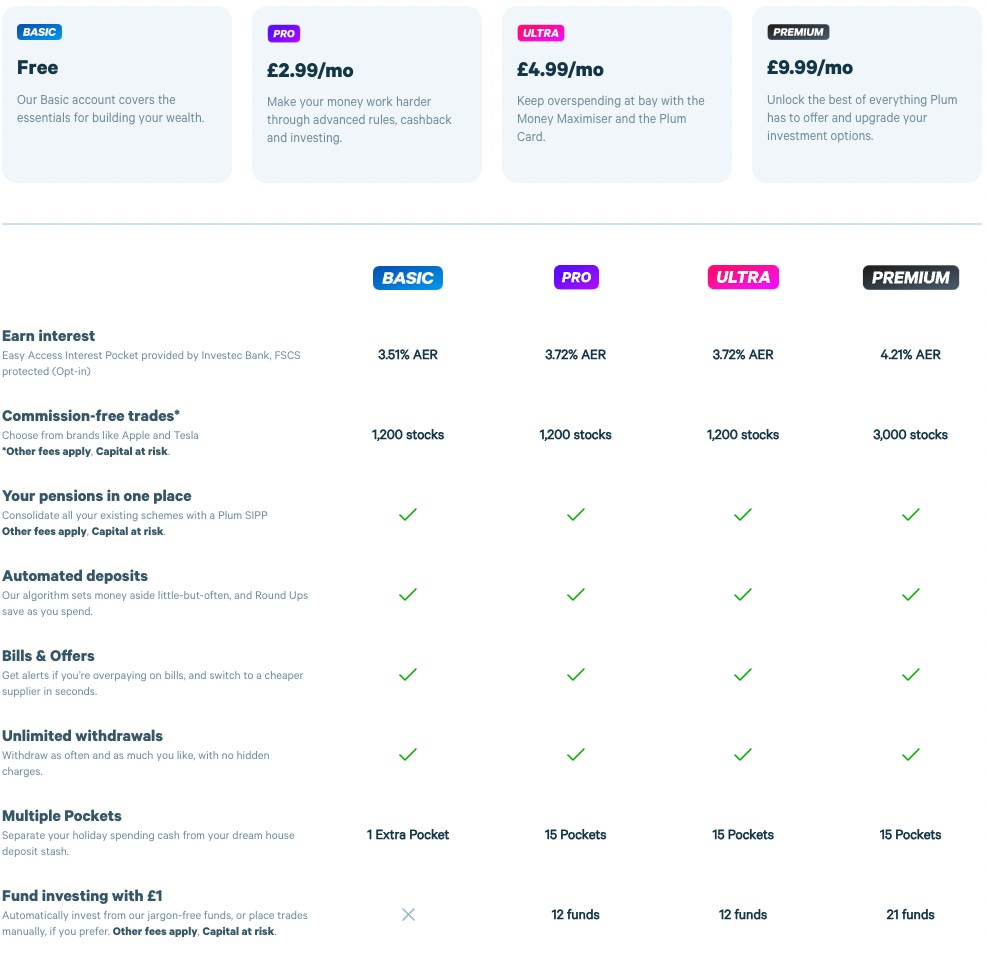

Licence + Fee (Subscription Model)

This is the classic model for B2C and B2B SaaS products, which charges a monthly or annual fee and covers all features within that given tier. It can be highly configured depending on the business with Lite, Standard and Premium tiers containing a progressively more valuable set of features or the tiering done based on the complexity of the end customer. Within this model, there is Flat Rate pricing, where a single flat fee is charged for the product or Tiered pricing (the more common model), where the product is split into different tiers and priced accordingly. Subscription pricing in fintech is a lot more prevalent in SME-focused propositions than retail consumer products.

Common Application: Financial Management, Accounting, SME Banking

Examples: Xero, Sage, Satago, Tide, Monzo for Business, NatWest Business Banking

Usage Based

In a usage-based pricing model, fintech companies charge customers based on how much they use their services or products. This can include charges for specific transactions, the volume of data processed, or the number of users. Used by providers that perform data-based services, checks or reports.

Common Application: Financial Data Providers, Infrastructure/API providers

Examples: Plaid, TrueLayer, Bud, Codat, Bloomberg, Claro Money

Take Rate (Percentage of transaction)

The take rate pricing model involves fintech companies taking a percentage of the value of each transaction conducted through their platform and, therefore, prevalent in high-volume and high-value transaction organisations, which is why it's one of the more popular pricing models in fintech.

Common Application: Insurance Products, SME Lending, Payment Processors, Investment Platforms, Crypto exchanges, FX, BNPL

Examples: Stripe, Square, Klarna, Wise, Adyen, Marqeta, Thredd, Public, Freetrade, Coinbase

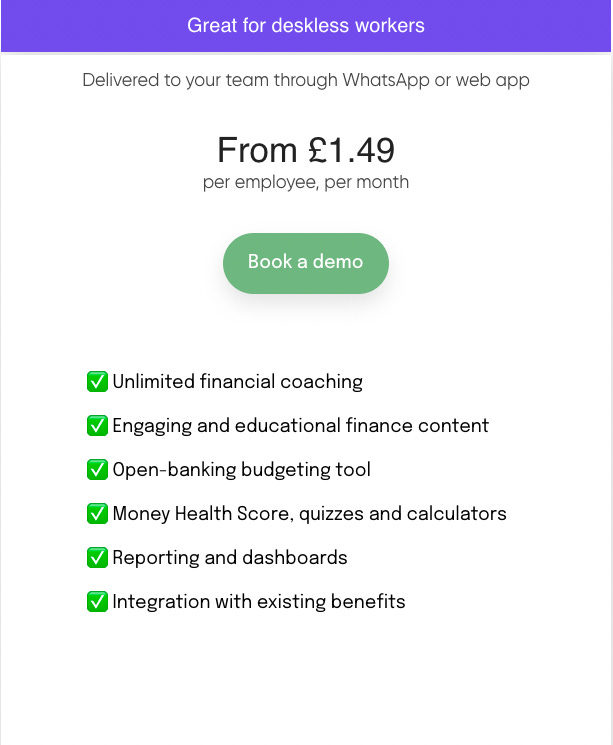

Freemium

The freemium pricing model is probably the most popular strategy in the B2C side of fintech, offering users a combination of free and premium services. It allows fintech companies to attract a wide user base with free access to essential features, allowing for a wide onboarding funnel while monetising their offerings by charging for advanced or premium features.

Common Application: PFM Apps, Retail/Digital Banking

Examples: Cleo, Plum, Emma, Monzo, Starling, Revolut, N26, HSBC, Lloyds

A key thing worth noting with these pricing models is they are usually not used in isolation or exclusively.

For example, although many Personal Finance Management Apps use the freemium model, the premium part of the offering is usually offered using a tiered subscription model.

And although the pricing model for merchant acquiring platforms like Square is largely a Take Rate model, part of its acquiring & retail management package offering is a Subscription + Take model.

What more mature platforms tend to do as they evolve and add more strings to their product stack is create a pricing model that reflects the different products. In Square’s case, a blended model for the retail package of take rate for transactions + subscription for the retail software reflects the benefits of each part of the package offering. Take rate for the ease of taking card payments and a subscription for the retail management software.

The Psychology of Pricing 🧠

In terms of the pricing discussion, I’ve definitely saved the best till last. And by best, I mean the section with the most “ahh, so that’s what that’s called” moments.

You won’t be surprised to know there are many tips and physiological tricks when it comes to the end product pricing page, which has also touched fintech. These techniques are designed to steer customers towards particular choices, increase conversion and improve conversion speed.

Here are some of the more interesting techniques.

Hicks Law and Choice Overload 🍟🍔🍕🌭🌮🥓

The formula for Hicks Law is as follows:

RT = a + b log2 (n)

The formula translates in simple terms to: The time it takes for someone to make a decision increases with the number and complexity of choices.

The law’s impact is seen on many websites, especially on pricing pages. Pricing and payments bring friction, and complexity brings more friction, so companies use many techniques to mitigate and reduce the impact of Hicks Law.

Keeping pricing options limited. Three is usually the magic number

Simplify the choice for customers by suggesting a ‘Recommended’ or ‘Most Popular’ option

Removing unnecessary text so as not to distract customers from the choice at hand

Artificial Urgency 🏃🏽♂️

Many digital organisations, and lots of offline ones, will create what’s called Artificial Urgency. You already know what I’m talking about.

-> Summer Sale.

-> Closing Down, Everything Must Go

-> 50% off this Weekend Only

-> Limited Stock

These are all examples of artificial urgency.

This false sense of urgency or scarcity around a product encourages potential customers to make a purchasing decision quickly, prompting immediate action by conveying that an opportunity is limited, and if the customer doesn’t act promptly, they might miss out on a valuable deal or product.

Although examples in fintech aren’t widespread, some do use Artificial Urgency (usually around Black Friday) to offer limited-time discounts on subscriptions or limited pricing for early adopters of a product, e.g. Only the first 5,000 customers will be able to sign up for this price.

Looks can be deceiving 👀

When it comes to pricing, psychology goes down to the level of the look and feel of the price itself, and a few tweaks have been made to prices to make them more appealing and to reduce price friction.

Using numbers with fewer syllables: Although when we don’t say the prices out loud, studies show that people perceive phonetically shorter prices as being cheaper

Removing the Comma: Research shows removing commas from prices can make a price seem smaller

Removing any other unnecessary digits: Removing any unnecessary zeros, decimal points, and currency signs has been proven to make the price seem smaller and reduce price friction. This is again down to the psychological trick and association between the time it takes to read the price and its numerical size

Visual contrast: Creating a visual distinction between an original price and a sale price (which is why many sale prices are red contrasted with the original price). The higher black and bold price makes the smaller red price more appealing

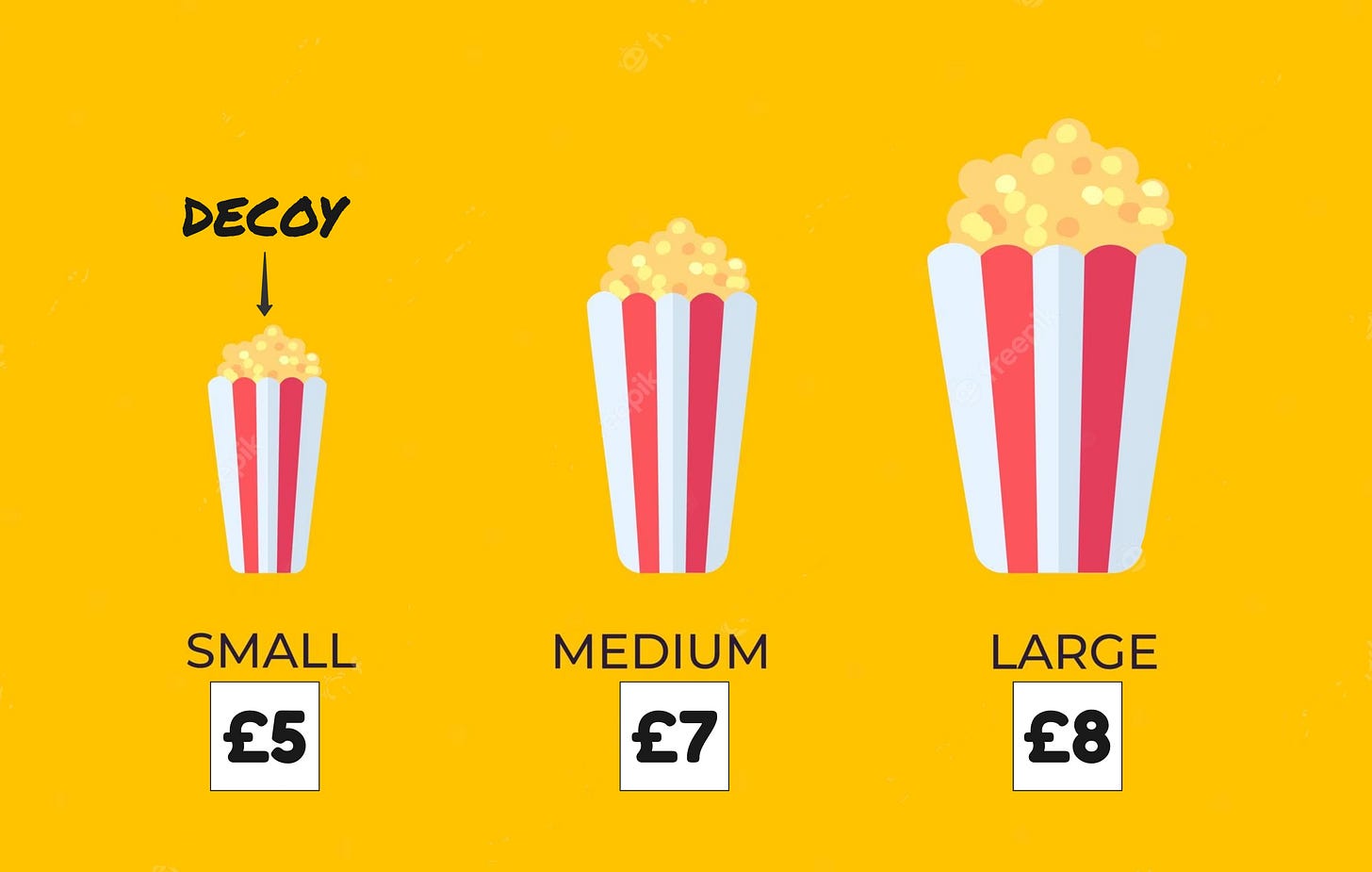

Decoy Pricing 🍿🍿🍿

Decoy pricing, also known as price anchoring, the asymmetric dominance effect, or what I like to call Popcorn Pricing because of the popular example, is a pricing strategy businesses use to influence consumer choices and maximise their profits. It offers three different product options to steer customers towards the most profitable choice by introducing a “decoy” product that makes the preferred option seem more attractive. The decoy is typically priced in such a way that it makes the target product appear as the best value for money.

As mentioned, the popcorn example is an ideal illustration of decoy pricing in action:

Small Popcorn: £5 for a small bag with 30 ounces of popcorn.

Medium Popcorn: £7 for a medium bag with 40 ounces of popcorn.

Large Popcorn: £8 for a large bag with 50 ounces of popcorn.

In this scenario, the medium popcorn is the target product, while the small popcorn serves as the decoy. Here’s how decoy pricing works:

The customer might initially be torn between the small and medium popcorn, as the price difference is insignificant (£5 vs. £7).

However, the large popcorn, priced at £8, is strategically placed to make the medium popcorn appear as the best value. The presence of the large popcorn makes the medium popcorn seem like a great deal, and many customers are more likely to choose the medium size over the small, thinking they’re getting a better value for their money.

The small popcorn is the decoy, as it is priced in a way that makes the medium popcorn look like a superior choice in terms of value. Then the customer can spend £1 more for 10 more ounces of Popcorn in the large option if they choose.

Popcorn pricing is applied across fintech products with a subscription where there is a ‘lite’ version priced with a set of features that makes the ‘Standard’ offering look the most cost-effective.

Outro

Coming full circle, there is no silver bullet for pricing decisions, and I’ll continue to start pricing conversations with “It’s complicated”, but there are a myriad of reasons why.

Product pricing isn’t just about finding a price that will lead to a high volume of customers.

It’s about finding the right blend of a pricing strategy that shows the value of the product, is cost-effective and competitive in the market.

It also means understanding the stage the company is at and its objective. Whether that’s to raise awareness for the organisation, undercut competition, maximise profits or embed a long-term customer retention strategy.

Selecting the right pricing model also depends on the company type, whether a high-volume transaction company, a low-volume B2B lender, a crypto exchange, an FX firm or a data provider.

Once at the level of the pricing page, a range of techniques and psychological tricks can be applied to get customers over the line, reduce friction, and increase conversion.

The point is that pricing isn’t just selecting a price and running with it. It needs analysis, a full-blown strategy and prices, with business strategy, change over time.

Doing all this underlying discovery work, competitor analysis, building an overall pricing strategy and using psychological pricing techniques could mean the difference between this…

…and this…

Interesting Fintech News

UPI Transactions - The end of August saw UPI transactions hit 10 Billion, up from the previous high of 9.96 Billion in July. The progress shows no signs of slowing down, with more international deals signed and adoption outside of India set to grow.

OneId raises 1 Million - Digital Identity is inevitable, and as much as it might seem a little big brother, there are many benefits, especially in the SME space, reducing friction for businesses looking to onboard clients and for SMEs looking for finance. This raise is likely in preparation for more partnerships and integrations in addition to the one announced with NatWest.

Public and AirWallex - Public, the US investing company that recently went live in the UK, has partnered with AirWallex to “use its financial infrastructure and global payment capabilities to create a “frictionless experience” for Public customers”. Partnerships are key to long-term growth, and partnership switching is expensive. In AirWallex, Public have found a partner that allows them to grow at pace and beyond the UK into European borders if that’s part of their long-term plans.