Fintech R&R ☕️ 📜 - The 411 on 1033. A US Open Banking standards deep dive

The new US Open Banking proposal, what it might mean for consumers and what the US learned from the UK's Open Banking successes and failures

Hey Fintechers and Fintech newbies 👋🏽

Slight change to the format going forward. I’ll start with a short set of ‘questions that will be answered’ in a cold open before diving into the full intro and edition. Let me know what you think, and if you like it, remember to click the heart button at the bottom of the page 🙂

What does Lisbon’s 1755 earthquake have to do with the US’s new Open Banking proposal?

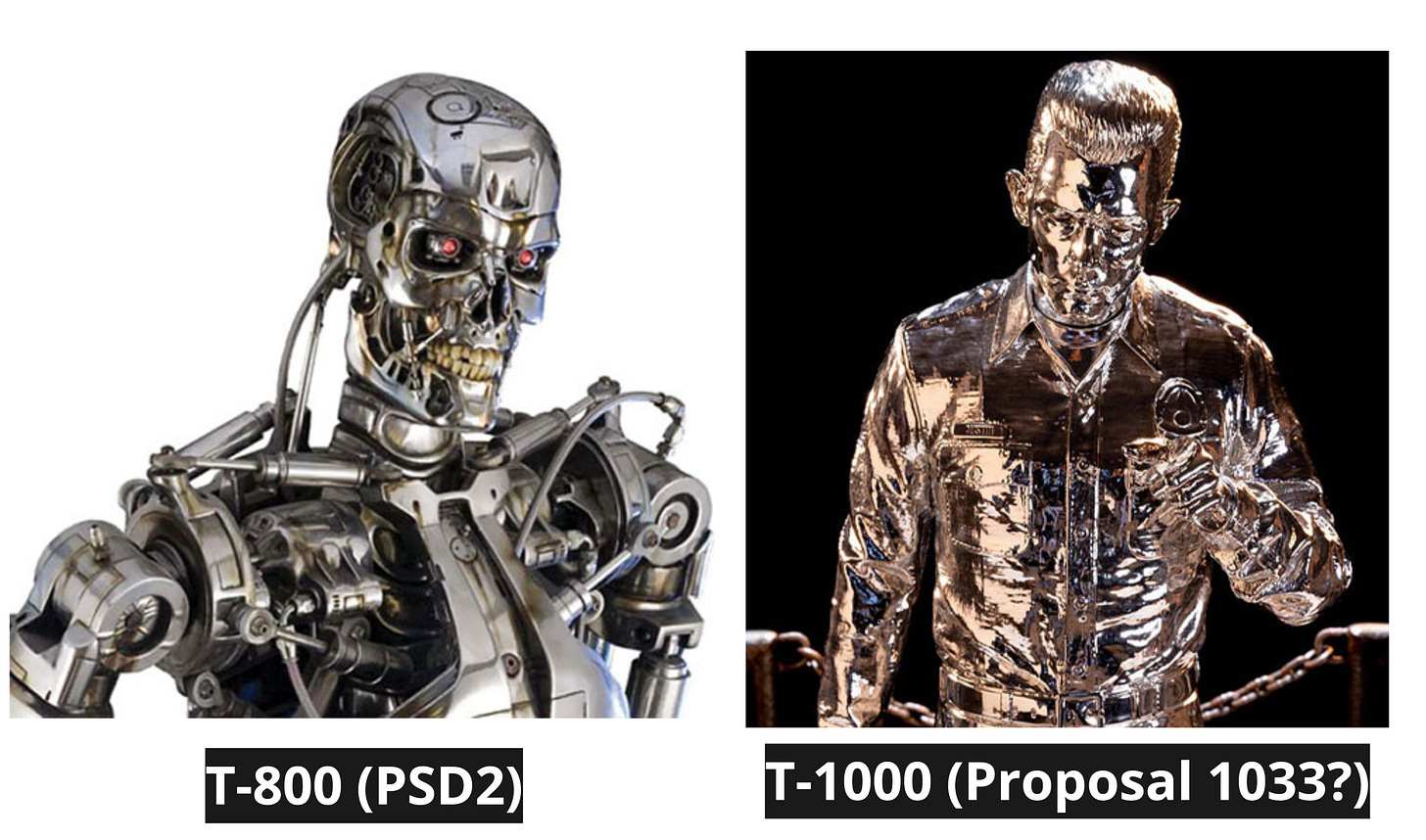

What connects the Terminator to the 1033 proposal from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau?

How can Jobs-to-be-Done be used to solve the problems in synergy with legislation?

What lessons does the US learn from the UK and EU member states implementation of PSD2 rules and Open Banking?

Will the 1033 proposal, the US’s ‘Open Banking Rule’, help solve some key consumer issues?

What are my thoughts on the shutdown of Mint by Intuit?

I answer these questions and many more in this week’s edition of Fintech R&R.

PS. This is a longer edition of Fintech R&R due to the subject matter and insights. To make sure you see the full version (some email clients cut off the end of the article), read it in your browser by clicking here and support my gruelling Thursday night write ups and late formatting sessions by clicking the like and share buttons :-)

PPS. If you’re at the FF Awards in London on Tuesday 28th Nov, please come and say hello. I’ll be wearing a very unique bow tie so I should be easy to spot.

Now let’s get into it 💪🏽

Last week, for my birthday, I was whisked away to Lisbon.

It’s one of my favourite cities as it has great weather, fantastic food, rich history, loads of activities, and the people are probably the friendliest of any city in the world (Tokyo are their closest rival, in my opinion).

It’s also a city that, much like London after the great fire, faced a colossal rebuild following the 1755 earthquake.

A little-known fact about the rebuild is that surveys were sent out to many citizens just after the earthquake to learn more about the exact timing of the quake, figure out areas that were impacted, and get more information to ensure a rebuild would be more resilient. This is a historical version of discovery work as part of a product development lifecycle.

It’s considered one of the first large-scale quantitative data collection exercises and the first part of Secretary of State Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo’s (Marquis of Pombal) three-part rebuild plan.

Part 1: This inquiry and understanding of the quake was called Inquérito,

Part 2: The restoration of order (Providências, or emergency measures)

Part 3: Rebuilding the city by introducing a new set of design rules and an architectural rebuild plan (Lisbon Plan)

The survey trickled down from the government to citizens via bishops and priests nearly 300 years ago is here. It’s a pretty interesting read.

“These facts are great Jas, but it’s Fintech R&R, not Lisbon R&R!”

I hear you. Here comes the fintech connection!

This Inquérito factoid and the Lisbon rebuild inspired me to finally cover the news released on 19th October about the formalisation of the US’s Open Banking framework, the seeds of which were first outlined in section 1033 of the Dodd-Frank Act in 2010.

This is why 1033 is nicknamed the Open Banking Rule, but more on that later.

In this edition, I dive deep into the proposal (as it is still a proposal with some Inquérito ongoing until 29th of December 2023), draw some parallels with the EU’s equivalent regulatory framework from 2016 (PSD2), describe the Open Banking implementation outcomes for the UK/EU members following PSD2, and talk about what lessons can be learnt from this and other implementations.

It’s the discovery work, research on other implementations and the current feedback being gathered that will hopefully build US Open Banking better and lead to better outcomes for consumers than the versions that have come before it.

And, of course, I’ll give my unique theory plus practice perspective on this as someone who has worked with founders to build using Open Banking technology.

So, as well as interesting news, puns + movie references, this edition includes the following:

A brief note on Dodd-Frank

What is it, what did it do, and what didn’t it do?

A full 1033 analysis with excerpts directly from the proposal

The key points

Main actors

The data items ‘given back’ to the consumer

Timeline

Parallels with PSD2 and UK/EU Open Banking

Real-world applications of a US Open Banking Standard

The name’s Frank, Dodd-Frank 🕵🏼♀️

Anyone working in and around the US banking system after the 2008 financial crash will have a reasonable idea of what Dodd-Frank is or at least have heard of it. I was working for a US investment bank at the time, building out some new technology for one of the trading desks, and Dodd-Frank was a common talking point on the trading desk and in technology strategy meetings.

For those unfamiliar with Dodd-Frank or have forgotten some of the key aspects of the act, this little refresher is for you.

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, commonly known as the Dodd-Frank Act or just Dodd-Frank, was a comprehensive financial reform legislation enacted in the United States in 2010 in response to the 2007-2008 financial crisis. The primary goals of Dodd-Frank were to enhance financial stability, protect consumers, and reduce the risk of another financial crisis.

Key provisions of the act included the following:

Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC): The creation of FSOC, which is tasked with identifying and responding to emerging risks within the financial system.

Volcker Rule: Prohibits banks from engaging in proprietary trading and restricts their investment in hedge funds and private equity funds.

Derivatives Regulation: Regulatory measures for the over-the-counter derivatives market to increase transparency and reduce systemic risk. This rippled through many FS organisations leading to standardised OTC contracts and resulted in technology changes across investment banks, hedge funds and asset managers. I’m acutely familiar with this one because I was involved in the resulting system changes whilst at Schroders.

Whistleblower Protections: Enhances protections for whistleblowers who report potential violations of securities laws.

Mortgage Reform and Anti-Predatory Lending: Measures to address issues related to mortgage lending, such as requiring lenders to ensure borrowers’ ability to repay and prohibiting certain predatory lending practices.

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB): The creation of the CFPB to oversee and regulate financial products and services offered to consumers, with a focus on protecting consumers from abusive practices.

I won’t go into whether each of these has been successful or not, as it opens a bit of a Pandora’s Box.

The relevance of Dodd-Frank to the US’s Open Banking framework is twofold. First, the creation of the CFPB, whose primary objective is ‘to ensure that consumers have access to fair and transparent financial products and services’.

Second, section 1033 of Dodd-Frank which addresses the issue of consumers’ access to their own financial information held by financial institutions. It allows consumers to access data in a format that is usable by them and that can be easily shared with third-party service providers if they choose to do so.

Here’s the key excerpt from section 1033 of Dodd-Frank:

“Subject to rules prescribed by the Bureau, a covered person shall make available to a consumer, upon request, information in the control or possession of the covered person concerning the consumer financial product or service that the consumer obtained from such covered person, including information relating to any transaction, series of transactions, or to the account including costs, charges, and usage data.”

The Bureau is the CFPB, and a ‘covered person’ is defined as ‘Any person that engages in offering or providing a consumer financial product or service’ or ‘Any person that the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (CFPB) determines by rule to be a covered person for purposes of this title.’

Until about three years ago, section 1033 of Dodd-Frank remained dormant with no rules from CFPB to kick this into action.

That all changed in October 2020 when the CFPB issued a ‘notice of proposed rulemaking’, a notice to tell people they’re building rules around section 1033. A round of feedback on those rules followed, which led to a more robust proposal announced last month and paired with a public statement.

1033 Proposal and new US Standards 📜

This recent announcement feels like deja vu, with much of the phraseology in this and the original excerpt from section 1033 echoing the intent and phrases in 2016’s PSD2 initiative, the equivalent of Open Banking legislation in the UK and EU.

For a deeper dive into UK/EU Open Banking and more info on PSD2, check this previous write-up.

Much like the formal announcement of the PSD2 proposals, this is the starter gun for standard Open Banking rails in the US and a wave of innovations as it makes it easier for innovators to build tools to solve real-world problems without the friction and cost of getting the data to power those innovations.

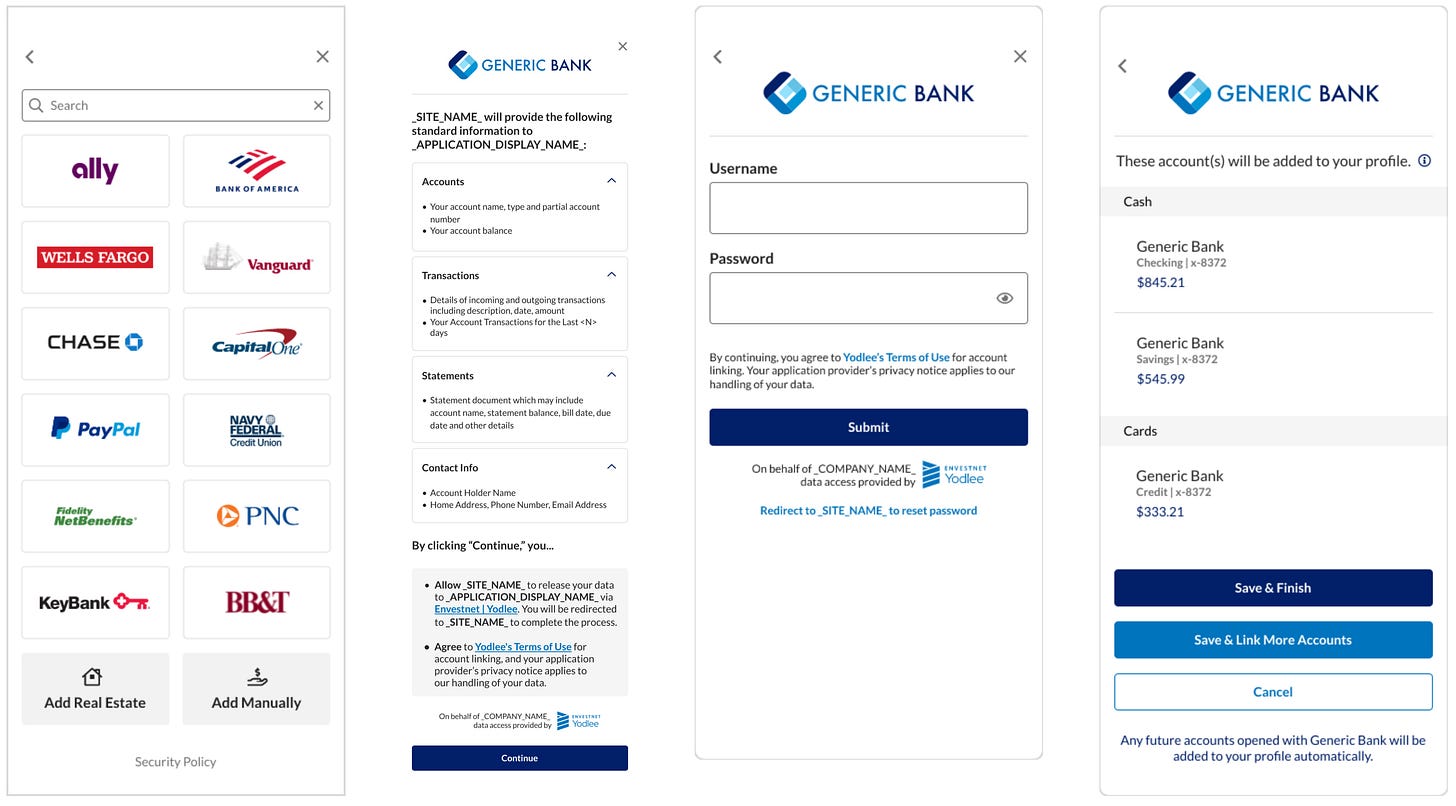

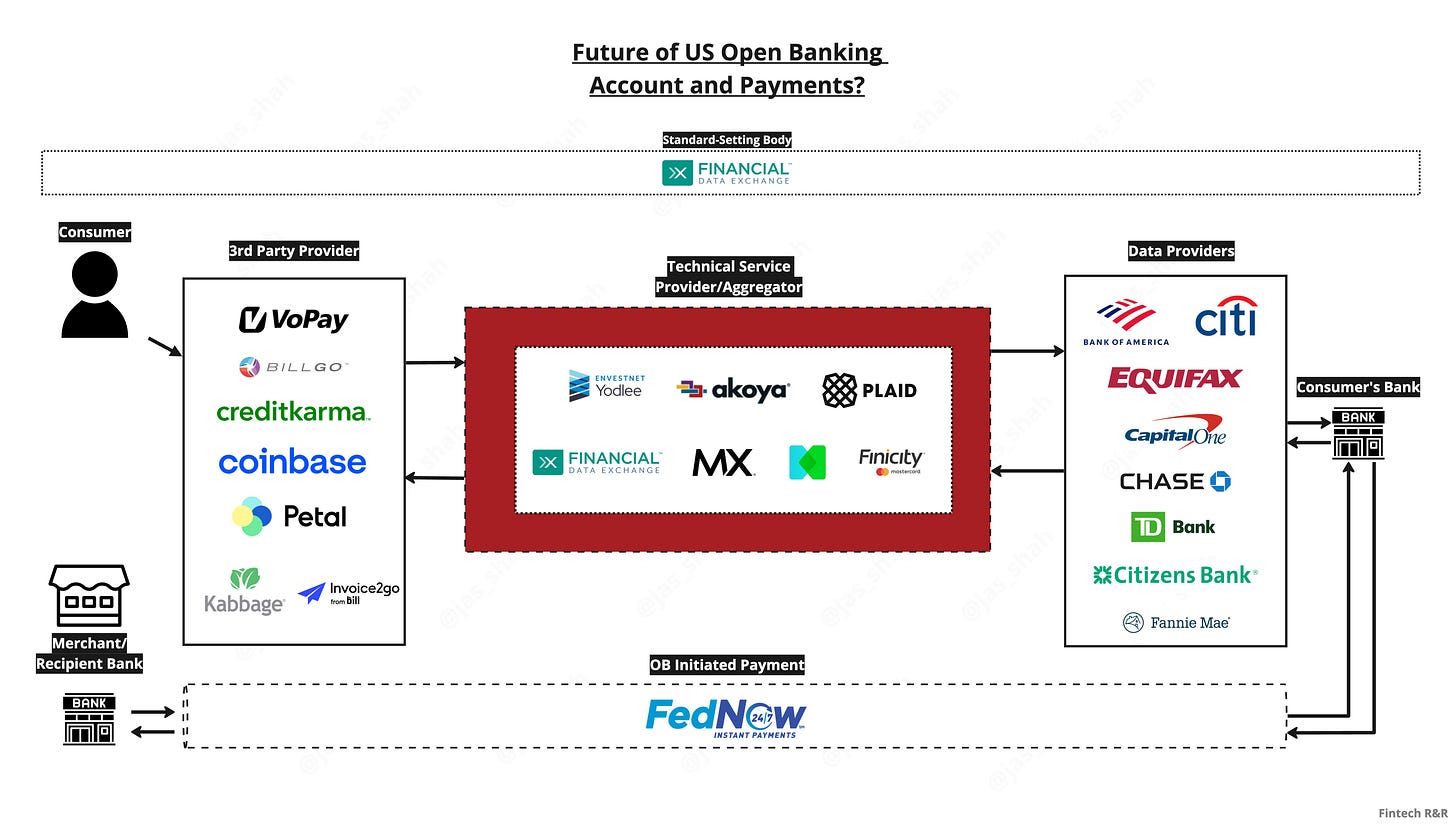

That’s not to say informal Open Banking processes haven’t been prevalent until now. Informal screen scraping, data collection and sharing is used by banks and facilitated by Third-party providers like Plaid, Akoya and Yodlee, but as you can see from the images below, much of the ‘standard’ process has just been ported over from the UK/EU standards and the bank coverage isn’t as high is in Europe.

So what is the 1033 proposal, who will it impact and what will it mean for consumers?

What is it?

The below is directly from the summary of the proposal released on the 19th October:

“The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) is proposing to establish 12 CFR part 1033, to implement section 1033 of the Consumer Financial Protection Act of 2010 (CFPA). The proposed rule would require depository and non depository entities to make available to consumers and authorized third parties certain data relating to consumers’ transactions and accounts; establish obligations for third parties accessing a consumer’s data, including important privacy protections for that data; provide basic standards for data access; and promote fair, open, and inclusive industry standards.“ - Rohit Chopra, Director of CFPB

It sounds pretty similar to the PSD2 opening summary and is not the only parallel…

Under this principle, depositary institutes such as commercial banks, savings institutes and credit unions would be impacted, as well as non-depository entities such as sales financiers, consumer lenders, real-estate credit providers, and credit bureaus.

Key actors 👥

The CFPB define the above group as ‘Data Providers’, and there are a couple of other terms to outline for completeness along with their corresponding responsibilities:

Data Provider/Covered Person: Entities that offer consumer financial products or services and hold information on the customer and product. Banks, lenders, savings account providers, etc.

Role: Required to make available to the consumer, upon request, information concerning the consumer’s financial product or service.

Consumer: The individual who has obtained a consumer financial product or service from a covered person.

Role: Has the right to request access to information related to the financial product or service.

Authorised 3rd party provider: External entities that consumers may choose to share their financial information with, as allowed by Section 1033. Usually, apps like PFM apps that use your data and add some value

Role: Once authorised, used consumer data to provide value in switching accounts, giving more visibility on

Aggregator: External entity that connects to various data providers and consolidates data for the 3rd party or consumer. Truelayer, Plaid, Yodlee etc

Role: Once authorised by the consumer or 3rd party, connect with and pull relevant data from the data providers

A standard-setting body: A fair, open, and inclusive body. Most assume this is the Financial Data Exchange based on the language used and the fact they already have a number of high-profile members with the goal of “common, interoperable and royalty-free technical standard…for data sharing.”

Role: Responsible for setting industry standards and adherence to those standards by key players

Again, there are lots of parallels with the PSD2 and early UK Open Banking from these terms and here’s the direct US to UK comparison:

Data Provider -> Account Servicing Payments Service Providers, or ASPSPs (Banks, Savings accounts, etc)

Authorised 3rd party provider -> Account Information Service Providers, or AISPs (PFMs, credit viewers, lending apps)

A standard setting body -> Open Banking Implementation Entity (OBIE)

Aggregator -> Technical Service Provider, or TSP (TrueLayer, Plaid etc)

The main ‘what is it’ of 1033 in a one-liner is that Data Providers, via Aggregators, Authorised 3rd party providers or directly, have to give relevant & sufficient electronic data back to Consumers through a developer interface, all governed under a single standard-setting body.

Phew. That’s a 299-page proposal summarised in a one-liner.

What data should be provided? 💽

Sufficient in terms of history of data is defined as a minimum of 24 months of historical transaction information where possible, and data providers will have an obligation to provide the following:

Latest and historical individual transaction information

Payment Amount, Date, Type, Pending or Authorised status, Payee or Merchant name, Rewards Credits, and Fees or Finance Charges

Account Balance

Credit card balance, account balance, and generally any funds in an asset account

Payment Initiation Info

Tokenized Account Number and routing number to be used to pay from or receive to a consumer account masking the original acc num (an area they’re still seeking some feedback on but could be a really interesting space and an overall fraud-reducing initiative)

Terms and Conditions

T&Cs of the product

Upcoming Bill Information

Bill source and amount due, including Credit Card bills and utility payments

Basic Account Verification Information

Consumer information connected to the product, such as name, address, email, address, and phone number, for the purpose of account and identity verification

There are a couple of general principles around accessing the data, such as creating a standardised format, ensuring they are ‘machine-readable’, the restriction on charging fees for the data, and maintaining a high response rate for any interface of 99.5% (percentage of successful requests across a given month). I won’t dive into these now, though.

Who and what companies and products does it cover? 🏦

I’ve touched on a few, but here’s what is defined as ‘covered organisations’:

Banks and Credit Unions: Traditional banks and credit unions that offer consumer financial products and services fall under the scope of covered persons.

Mortgage Lenders: Entities that provide mortgage products and services to consumers are covered.

Credit Card Companies: Companies that issue credit cards and provide related financial services are covered.

Non-Bank Financial Institutions: This category includes various non-bank entities that offer consumer financial products or services, such as payday lenders, check cashing services, and other similar institutions.

Fintechs: Online and digital financial service providers, including fintechs that offer consumer financial products or services, are covered.

Auto Lenders: Companies providing auto loans and related financial services to consumers are covered.

Student Loan Servicers: Entities involved in servicing student loans for consumers are covered.

Debt Collectors: Entities engaged in debt collection activities related to consumer financial products or services fall under the definition of covered persons.

One large caveat to all the above data providers is that they are only obligated to provide data under 1033 if they already have a digital interface for the consumer. So, if they don’t already have a consumer-facing digital banking interface, they are not subject to any of these rules. This is one of the explicit exclusions outlined in the proposal.

Using a UK Open Banking diagram I put together a few years ago, here’s what a similar view of US Open Banking could look like in the future although much of this is already working as shown below with some key actors excluded…

What is the overarching objective? 🎯

There are some objectives outlined in the proposal.

Getting rid of screen scraping

Establishing standards for data access

Promoting fair, open, and inclusive industry standards

Clarifying the scope of data access

However, the broader objective is to give ownership of financial data back to consumers and 3rd parties authorised by consumers through a clearly defined, secure, scalable route, making the market more competitive and allowing customers to make informed decisions about products and pricing that suit their circumstances.

The ‘giving ownership back’ is the ‘Open’ part of Open Banking.

Next Steps? 🛣

The proposal is currently being reviewed, and the feedback-gathering session closes on the 29th of December.

It will likely have some amendments based on feedback and a final, shorter review period, with the entire proposal likely formalised in Fall 2024 (before the November election).

The Financial Data Exchange will probably be appointed the standards body, and large institutes such as banks and lenders will have six months from the passing date, which I guesstimate to be around April 2025 to adhere to the new rules. Medium and small institutes will have a bit longer to ensure adherence to the new rules.

Well, that’s the 299-page proposal in a nutshell. I’d be lying if I said that it includes every detail, but it does contain the important details, the intent of the proposal, affected parties, key beneficiaries and the projected timeline.

The big questions are: 1. Will it be a net positive, and 2. Does 1033 use lessons learnt from EU and UK Open Banking?

Let’s start with whether there are lessons learnt.

US and UK (and EU) relations 🇺🇸🇬🇧🇪🇺

The short and fence-sitting answer to whether 1033 improves and takes lessons from PSD2 is…..yes and no. Here’s the reasoning behind my non-answer with a 1-3 thumbs up or down rating system.

Payments 👎🏽👎🏽

Part of the 1033 proposal talks about Tokenized Account and Routing Numbers, which is great, but it doesn’t say anything about using them or, payment initiation in any form. It means you can share secure tokenized details with another person or organisation, but they have to use a different service to send money to that account. Definitely a missed opportunity, especially with the launch of FedNow and the parallels that can be made with UKs Payment Initiation Service using Faster Payments.

Identification of a Single Standard-Setting Body 👍🏽

The Open Banking Implementation Entity is seen as one of the driving factors for the early success of Open Banking in the UK and is regularly cited by other global OB initiatives as a great example of the governing body that drives change. The identification in the proposal of a need to appoint a standard-setting body, whether that’s FDX or someone else, is a great example of following the lead taken by CMA9 by creating the OBIE and giving a single external body responsibility for upholding rules and hopefully driving change for consumers.

Jobs-to-be-Done analysis and outline key stating them in the proposal 👎🏽

There is deep analysis in the proposal of some consumer problems, wider market issues such as the security concerns around screen scraping and a broad stroke when it comes to financial data ownership and usage, but I wish it went a bit further. One of the things I was looking for as part of the OBIEs plan and the approach of early Open Banking innovation was some independent and complementary analysis into broader issues that the implementation of Open Banking can help with. For example, mortgage rate switching tools to ensure a data-first approach to switching mortgages at the most cost-effective time for homeowners. Or an issue facing many in the Western world which is a deepening of poor financial literacy with younger generations and dedicated research and problem statements that help guide innovators to use the technology to tackle those issues.

It’s slightly Big Brother and maybe goes against how regulation is outlined, but there’s no good reason why supporting whitepapers can’t be produced with guidance as to what the key problem areas are and maybe some funding in key categories to go with it?

The “let the market dictate innovation” approach can work, but in this case, I prefer the “set some guidelines to accelerate solutions in specific problem areas” backed by some JTBD analysis, which helps innovation across different areas rather than focusing on just one.

Broader Account Scope 👍🏽👍🏽

The initial PSD2 rules that flowed down the EU member states in 2016 initially focussed on payment initiation and account information access to current accounts. Not credit bureau data. Not savings accounts. Not credit cards. Many saw that as a misstep. The 1033 proposal doesn’t make that same misstep as the prior ‘covered organisations’ section outlined. Ensuring the standards ensure greater competition across a wide range of financial products, not just current/checking accounts, is a positive move. It also allows for a broader scope of innovation rather than just account comparison tools or Digital Money Managers (DMMs), aka Personal Finance Management (PFM) tools.

Generally, I think it’s pretty balanced in terms of lessons learned. Payment initiation is the glaring omission from the proposal, but considering they want to get this passed before next year’s election, I can see why they left it out. The biggest responsibility is driving this forward and ensuring standards are rolled out and held consistently across all organisations. If it is FDX, it probably helps that 65 million consumer accounts are already connected via the API they’ve built.

NB. I haven’t seen the FDX API, so I can’t comment on what, if any, changes they’d need to make if theirs is to be the gold standard developer interface of choice, but that might come if and when this proposal is cemented.

Real-world applications 📱

Before diving into what is frank-ly my favourite section of the newsletter each week, where I get creative with my fintech product & digital strategy experience, there are a few key points to highlight.

As mentioned, there is a popular Open Banking API that covers the USA and Canada run by FDX, but it’s not mandatory for all organisations (until the proposal comes into force), which means building products with wide reach that solve problems en masse is tough until many more institutes are signed up.

Another point to highlight is that in the UK, it was the CMA9, the largest 9 banks in the UK, that fronted the cost of changes to systems to make data available, and in May 2021, it was reported that they spent a combined £26 million to help support promotion of Open Banking reforms. The CFPB has openly admitted that the “largest costs will come from data providers establishing and maintaining compliant developer interfaces”.

These are to highlight that although the general agreement is that this will benefit data providers and consumers, the costs and effort will primarily be on the data providers, and the benefit will vastly skew in the direction of consumers.

I think this is fair given the fact that, generally, banks and large FIs have provided financial products BUT not an adequate set of tools to consumers.

Rohit Chopra, the director of the CFPB, said in a supporting press release that the proposal is designed to “accelerate much-needed competition and decentralization in banking and consumer finance by making it easier to switch to a new provider.”

Switching providers is a use case, but I don’t think it’s even in the top 10 of consumer problems. Here are some higher-priority issues that I hope a broad open banking standard will help with.

Financial Education and Literacy apps 📚

Every year, there’s a report talking about financial education and the lack of financial literacy at the grassroots. There’s a boom in financial literacy products and services. GoHenry and Rooster are good examples for children and young teens. There are also many grant funding initiatives to support the building and growth of digital products to solve this problem in the UK. But the problem still exists for the young teen market, and the longer the issue goes on, the more people will be left behind.

I’ve said this in a previous edition, but research shows the problem is getting worse with millennials and Gen-Z being less literate and comfortable with managing finances than their boomer predecessors.

In a study by the TIAA, Gen Z respondents averaged the lowest (43%) in answering finance-related questions correctly

Almost half (45%) of the UK adult population lack confidence when managing their money

Financial skills among the under-34s, on average, are 16.5% lower than the national average

A study in the US proved that lack of financial knowledge can literally cost you money.

Creating tools that use transaction data provided by standardised Open Banking rails will go a long way to helping reduce this ever-increasing literacy gap and, rather than Personal Finance Management, create a wave of Personalised Financial Education products.

Student Finance Management 🧑🏼🎓

There is another mention of Frank, but this time, it’s not prefixed with Dodd.

Frank was a US financial aid app, lauded by many and bought by JP Morgan Chase in 2021 for $175 million. It was a product that helped college students apply for financial aid. The only problem was that Frank had inflated its registered student numbers, and then drama and a lawsuit ensued.

However, it was solving a key problem for students. It was just solving it for ten times fewer students than it stated.

There is still a big problem there otherwise, JPM wouldn’t have thrown $175 million at it.

Of course, there’s the problem of sifting through the different student aid options and then applying for them. This is something that Frank did, and more products can do with the aid of an Open Banking standard.

There is, of course, the elephant in the room, and I’m not talking about the Republican logo.

In total, there’s $1.75 trillion of student debt. The average student owes $28,950. It’s probably the only situation where you commit to such a large financial outlay and don’t think about the consequences till three years later (I’m talking from experience).

Standardised Open Banking rails and accessible APIs make a student finance planning product easier and cheaper to build and give prospective students a better understanding of the cost of college.

US-UK and Broader Tax Calculations 👮🏼

Yup. Dreaded Tax management.

Talk to any overseas US citizen about investing, saving, or any other financial transaction that involves tax, and their eyes widen in horror.

That’s because US citizens are required to report income earned abroad in any foreign country of residence. This, along with the complicated tax codes, different treaties with various countries, and the need to still comply with local tax laws, makes submitting an accurate tax record to the IRS a complicated affair.

There are nearly 160,000 US citizens in the UK.

Imagine a digital bank in the UK that enabled these expats to connect their US bank accounts, get a single view of their finances, and give them the tools to generate an accurate filing for the IRS.

I’m not sure if the cost-benefit fully works out for a digital bank, but a small-medium sized SaaS accounting platform offering the ability to do a lot of the heavy lifting for US citizens’ tax returns could charge a premium to solve this problem for customers for a bit of upfront effort.

These are just three broad areas where a US Open Banking standard would increase innovation and competition, meaning JPM wouldn’t have to put $175 million worth of eggs in one basket.

It only takes a bit of discovery to uncover dozens more unsolved problems for consumers and organisations.

I haven’t even touched on topics like car finance, mortgage feasibility, microlending, POS e-commerce finance, SME lending, an interconnected global Open Banking network and the ever-looming $7 trillion opportunity, embedded finance. These are areas that deserve a separate breakdown.

Although UK Open Banking has some critics, it’s responsible for 100s of successful consumer-facing products and is powering the backend even more, so it’s a good sign that the US’s proposal takes some learnings from the UK’s implementation.

In terms of the consumer side benefit, there’s a lot to be hopeful for.

More will be revealed in the new year, which will probably warrant a further edition, but in the meantime, I’ll be watching, waiting, and come fall 2024, hopefully not commiserating.

Favourite bits of news

Following Intuit-on Budgeting - Personal Finance Management takes a bashing, but the problem of budgeting still exists for consumers. The issue isn’t the package of features. It’s that many providers haven’t found an economic model that works. It’s clear from surveys and research that, generally, customers don’t want to pay for dedicated budgeting and PFM tools, so organisations should see vanilla PFM products (those with budgets and transaction categorisation) as loss leaders because of the extremely tight margins or as an acquisition tool that sits atop the customer acquisition funnel. In the case of Mint, I think it was a matter of picking the app to invest the time, money and resources on, and they picked Credit Karma.

Starling’s Engine taking flight - Australia’s AMP Bank and Salt Bank in Romania are Engine’s newest clients, maybe proving that a BaaS model for smaller markets is feasible. Starling’s BaaS offering will power Salt Bank’s new app and will be used for digital onboarding, accounts, payments, and managing lending products. Although BaaS seems like a saturated market, many players target large-scale clients in mature markets, so Engine could be the full-stack provider of choice for new digital banking innovations in smaller but growing markets.